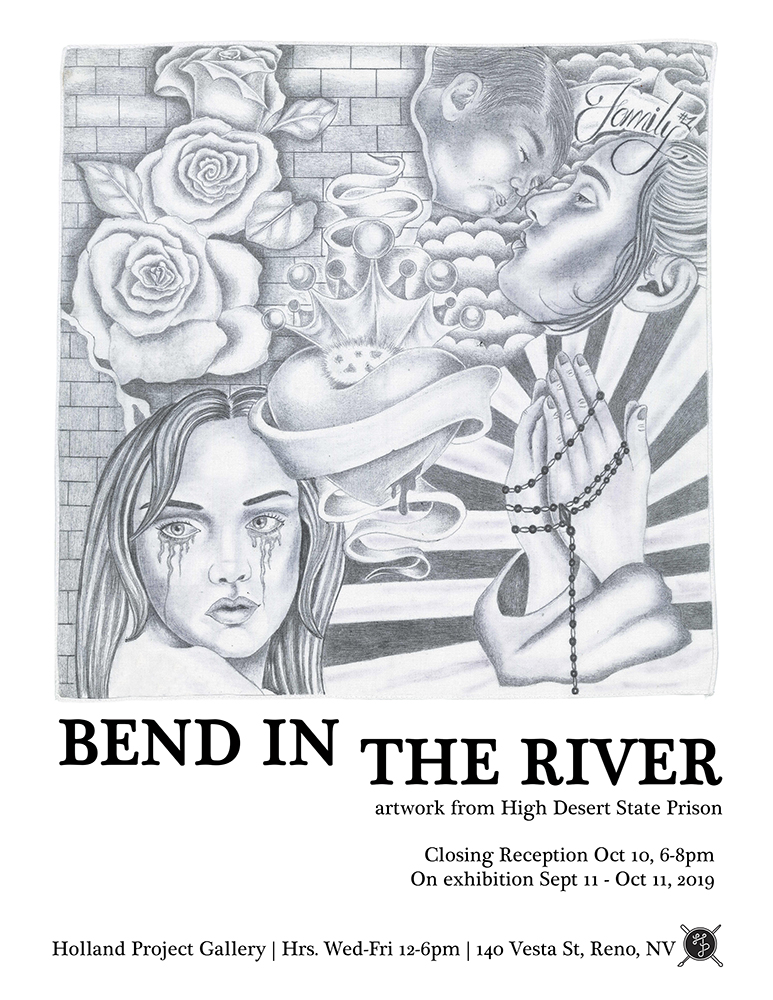

Over a year ago, The Holland Project hosted an exhibition titled Bend in the River, featuring the artwork of inmates from High Desert State Prison in Susanville, CA. The exhibition was organized by local artist Joan Giannecchini, who spotted this immense talent while working with the prison leading workshops in nonviolent communication. I had the pleasure of sitting down with Joan (on a bench in the sun, along the Truckee River in Downtown Reno) to talk a little more about the workshops she conducts, the challenges presented by the prison, and the ways in which she has adapted to the pandemic.

Being raised around violence herself growing up in California, Joan originally attended the AVP workshop in her own community three times before becoming a facilitator. AVP (Alternatives to Violence Project) is a grassroots worldwide movement committed to building peace within our homes, schools, institutions, and communities to foster positive transformation. Their workshops use the shared experience of both participants and facilitators to examine how injustice, prejudice, frustration, and anger can lead to aggressive behavior and violence, while also exploring our innate power to respond in new and creative ways. Joan explained to me how the organization was started by a group of Quakers who organized their first non-violence workshop at Greenhaven Prison, NY in 1975. The workshop was developed by both Quakers and inmates in response to the riots at Attica prison in 1971: the largest prison riot in American History that left 39 dead and 89 more seriously injured. Word spread fast of the workshop’s benefits, and it was soon introduced throughout the entire New York prison system. Today, AVP workshops are present in 35 states and over 40 countries.

Joan has been involved with the AVP for almost ten years now, becoming the team coordinator for the three and a half-day workshops conducted at High Desert State Prison. She tells me that on her first day visiting the prison, she nervously dropped a box of art supplies in a room full of inmates and was rather surprised when they all bent down to help her clean up. One larger inmate with face tattoos also intimidated Joan, that is until they recognized each other’s Italian last names and proceeded to bond over their grandmother’s recipes. Though inmates tend to segregate themselves everywhere else in the prison, AVP workshops are attended by individuals of every race and gang. “And when they are with me”, Joan says, “ – especially being a woman, everyone wants to be the gentleman.”.

She tells me how she can gauge the level of participation in observing the posture of students. On their first day, some stroll in with young cool confidence and slouch in their chairs. On their third day, Joan says, most are fully engaged, leaning forward with their elbows on their knees. Not only does Joan share her own story with the workshop, but she often finds herself inspired by the powerful stories of her students as well. They’re encouraged to share their stories no matter how intense. One critical component of the workshop addresses how violence was handled in the home of an individual growing up. It also teaches participants how to work through these situations of stress, turning them into opportunities for healthy productivity in expressing themselves and their experiences creatively. Many choose to draw, paint and sculpt, while others may choose to write poems, lyrics, and music.

When it comes to creating art while detained by the government, inmates are faced with multiple obstacles and limitations in materials, content, and compensation. No metal is permitted, which means no traditional paint brushes or oil paint itself, and rarely acrylics. Only materials special ordered from Blick and approved by the warden may be used. All artwork that leaves the prison must also be thoroughly inspected by a specialist who looks for hidden messages, paraphernalia, or explicit content. If prohibited material is found, it is immediately confiscated, and most likely destroyed. Joan tells me that months before the scheduled exhibition at Holland Project in 2019, correctional officers performed a “shakedown” on inmates. The all-inclusive prison search was likely instituted by the California State Department of Corrections, which permits x-ray machines in the gyms to check the bodies of the inmates and thoroughly tossing their cells in a search for contraband. Personal belongings and effects are not off-limits and can be destroyed at the discretion of the corrections officers. Some of the art produced for the Holland Project show was destroyed during this search and had to be remade. Inmates held in America are also rarely allowed to sell their artwork. Those looking for compensation may gift their artwork to a family member or friend, who could essentially sell their work on the outside. Funds may be deposited to inmates’ accounts to be used at the commissary.

Prison systems everywhere have been drastically affected by COVID-19. Joan tells me that inmates are just now receiving vaccinations, and it has been almost a year since she has visited the prison to conduct a workshop. In response, she has been working on developing art-exercises to distribute to the inmates for them to work on themselves. She doesn’t like to call them lessons, as a number of prisoners have learning disabilities, others suffer from illiteracy and mental challenges. They are meant to entertain more than teach, but still offer exercises for those who wish to be challenged. She just finished her first packet of exercises that focus on mark-making and texture, with demonstrated drawing techniques and sample photos of famous artworks to recreate. Joan has also been granted uncommon access to communicate with inmates to acquire their feedback on her guided exercises and to let her know what they would like to see in the future. Joan has always been able to sense when an individual has a genuine will to change; whether in hearing them tell their stories or experiencing their creativity first-hand. She is confident that the AVP workshops succeed not only in lowering the rate of violence in prisons, but at re-introducing individuals to society outside of prison and reducing recidivism as well. Please visit thejusticeartscoalition.org to learn more about this national network for artists in and around the criminal legal system, as well as avpusa.org to learn more about how you can get involved with AVP workshops for prisons, communities, youth, and trauma groups. If you would like to learn more about the many intricacies of the American prison system, The Holland Project has uncovered a number of zines on topics such as women political prisoners and prisoners of war, historic guides on “PP” and “POW” support, as well as writings from women in prison.

ARCHIVE: Bend In the River Exhibition Images

PURCHASE: Bend in the River Exhibition Catalog

______________________________________________________________________________

Contributor –

Otis Heimer

Otis Heimer received a BA in studio art from Principia College, Illinois in 2018; where he also served as teaching assistant and assistant curator for the James K. Schmidt Gallery the following year. Moving back to Reno in 2019, he is currently on track to receive his master’s degree in museum and gallery management from Western Colorado University this spring. You can follow his drawings on Instagram @hella.friggin

Cheryl Trottier

Mar 5, 2021 -

Very interesting read . Also very encouraged that the AVC programs seems to have wide spread success toward fostering positive transformation.